The Third Bird

Pure attention, the essence of the powers!

Distracted by each day's doing,

how can we hear the signals? - Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus

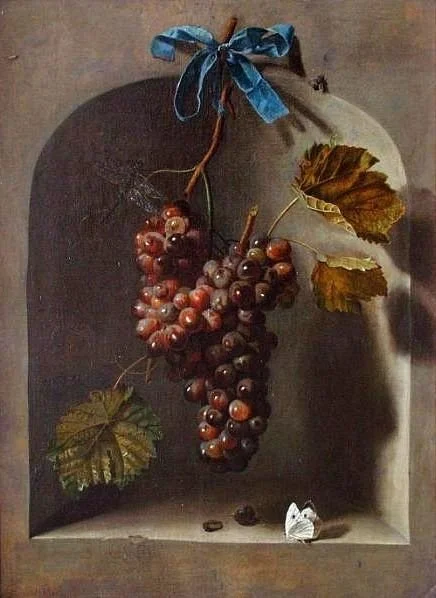

The Grapes of Zeuxis - David Vincent Wheeler

In his extraordinary article for The New Yorker, “The Battle for Attention,” Nathan Heller examines our diminishing capacity to pay attention to anyone or anything for longer than eight seconds. Among other startling findings sourced from academic and scientific researchers, the article reports that eight seconds is the average length of time we spend looking at an image on social media, 47 seconds is the average length of time we spend on any single web site before moving on, and that “attention problems” among young people, like ADHA, have tripled between 2010 and 2022 (“with the steepest uptick among elementary-school aged children.”) The article spends time thoroughly researching the way advertising companies are studying the trend of loss of attention for clues as to how to hook consumers with less and less time to do so. No surprise - this is a booming business.

In one of the more provocative suppositions in the article (and one I wish he had spent more time on), Heller cites the work of D. Graham Burnett and Justin Smith-Ruiu who posit that, contrary to prevailing opinion, technology isn’t the cause of our loss of attention. They point out that throughout history technology is a response to a human need. Implied is the idea that we humans created an avalanche of stimuli and needed new technology to keep track of it all. It’s as if we became addicted to “more stuff”, and invented the needle and tourniquette most effective for injecting it.

Loss of attention has a brother: multitasking. In her article for VeryWell Mind, Kendra Cherry writes that when multitasking “it might seem like you are accomplishing multiple things at the same time, but what you are really doing is quickly shifting your attention and focus from one thing to the next.” The idea that multitasking is somehow evidence of increased productivity is nonsense. “Multitasking takes a serious toll on productivity. Our brains lack the ability to perform multiple tasks at the same time . . . Focusing on a single task is a much more effective approach for several reasons.”

Heller spoke to teachers in higher education about this plague. He quotes a teacher who reports having to teach his students how to pay attention - something he only recently realized he had to do. Think about that. High school students do not know how to pay attention - to lectures, to readings, to research, to . . . art.

The bulk of Heller’s article is about a shadowy organization called The Order of the Third Bird.

The Order of the Third Bird takes its name from the following apocryphal tale: Zeuxis, a skilled painter, completes an image of a boy carrying grapes. He then leaves it outside and hides in the bushes to observe how the birds might treat it. Three birds approach. The first pecks at the fruit, and the second spies the boy, is frightened, and flies off. Zeuxis happily determines that with this painting he has finally achieved true verisimilitude. A third bird, however, stops in front of the painting and assumes a pose of contemplation, seemingly lost in thought. This third bird, the one who stops to contemplate a work of art, neither falling for it nor flying away, inspired the Order to formalize a practical esthesis in which an assembled body of viewers attempts to Encounter, Attend to, Negate, and finally Realize a made thing, focusing entirely on the object itself and not its history or meaning. ESTAR(SER), The Order for the Third Bird.

The Grapes of Zeuxis - Greek vase painting

It’s the coolest secret society in the world. Through introverted means, groups of people collect as volees - chapters within the order, so to speak. Anyone in a chapter may announce an “action” and summon the Birds to a location at a specific time. Once there, the Birds do not speak or acknowledge each other, but through a process of mutual attention collectively discover the object at the center of the action. Then, they go through a sequence of seven minute long “phases:” Encounter, Attend, Negate, Realize. After, they retreat to a location (like a coffee shop or a restaurant) for the Colloquy, where they share their experiences of the action with each other. The Birds feel that the Colloquy is the most important part of the action. If you want more detail about the activities of The Order of the Third Bird, read Nathan Heller’s article. All I know is - I desperately want to join. But, as a member put it, “it’s a Fight Club thing . . . the first rule of the Birds is that you don’t talk about the Birds.”

Recently, I had a free Saturday with nothing to do. So I took myself to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I spent a little more than two hours there, roaming through various galleries, stopping and attending to various works of art. I doubt I spent seven minutes with one artwork, much less 28 minutes as the Birds do. But over and over I did fall into the delicious and intimate revery of object and observer, when for a moment nothing else mattered but a painting and me, and a spontaneous intercourse between us unique to that time and place. Over and over, those works of art gave me an intimate gift personal to me, which I can never describe, activated by my attention.

Resisting empire requires action. Bridge-building between conflicting positions requires action. Healing trauma requires action. And cultivating attention requires action. One of the features of our current attention deficit culture is that the technology we jump about in makes us passive. I sit like a mannequin with animatronic fingers and dead eyes, scrolling . . . scrolling. What I love (among many things) about the Order of the Third Bird is that it is a peaceful call to action. “Come!” they chirp. “Let us flock together, and attend to the beauty and wonder of the world!”

I am grateful to have been trained as an actor, a way of being which rests on the exquisite attention actors pay to each other. I have spent my life bringing that quality of attention to others through classes, workshops, rehearsals and shows. Let us prioritize the giving and receiving of attention, and let us support young ones in developing their own attentive practices.

If not us, who? If not now, when?

“Attention is the most basic form of love. By paying attention we let ourselves be touched by life , and our hearts naturally become more open and engaged.”

― Tara Brach, Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life With the Heart of a Buddha

Barend van der Meer (1659-c.1702), Bunch of grapes hanging in front of a niche.